This piece was featured in issue #5 of Like the Wind Magazine. Words by Adharanand Finn – illustration by Luke Waller.

“It’s the greatest race you’ve never heard of: the Hakone Ekiden. Lots of races may lay claim to this impressive title, but few have such a legitimate case. On 2 and 3 January every year, this local university road relay brings Japan to a standstill. Raced over 135 miles, from the centre of Tokyo to the foot of Mount Fuji and back, it is a competition with more hype, emotion, and drama than any other race I’ve ever witnessed. The New York Marathon is a Sunday picnic in Central Park compared to this.

I arrive at 7 am on the morning of the race – on a national holiday – and already the crowds lining the streets are ten deep. University bands and cheerleading squads stomp and yell, the male cheerleaders waving their arms in what looks like some form of exaggerated semaphore. High overhead, helicopters appear and disappear between the cut-glass skyscrapers.

I arrive at 7 am on the morning of the race – on a national holiday – and already the crowds lining the streets are ten deep. University bands and cheerleading squads stomp and yell, the male cheerleaders waving their arms in what looks like some form of exaggerated semaphore. High overhead, helicopters appear and disappear between the cut-glass skyscrapers.

I find the first-leg runners down a quiet side street, pacing back and forth like boxers before a fight, wearing long, shiny jackets against the freezing temperatures. To an outsider, they’re just kids – university students, thrown into this melting pot of excitement. Their eyes look around, nervous. This may well be the biggest moment of their lives.” Certainly, unless they go on to win the Olympics, it will be the most important race of their careers.

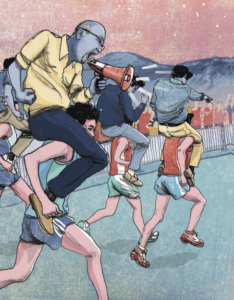

Waiting behind the runners is a squadron of cars, each vehicle with a megaphone attached to the roof. Men, older men, stand beside them, ready to go. These are the coaches. For many of them, their jobs are on the line today. Do badly at Hakone and you may be out of work. Do well and the bigger teams will be after you. Like Premier League football managers, coaching Hakone teams is not a job with much security.

And the megaphones? They’re for blaring out instructions at the runners. If they start to slacken, allowing a gap to grow between them and their rivals, or if they’re not catching up quickly enough, the coaches will let them know. And some of them don’t hold back. Later, in the media room, the Japanese journalists laugh and shake their heads at the screaming coming from one of the cars.

“What’s he saying?” I ask.

“It’s evidently not repeatable. ‘Bad things,’ is all they say. ‘Bad things.’ On the Japan Running News website, the writer won’t go into details either. ‘Throughout the race,’ he writes, ‘head coach Hiroaki Oyagi [of the Komazawa University team that finished second] shouted and screamed things at his runners from a loudspeaker in his chase car that would get a coach in the NCAA [the US college running system] fired.’ But while they may be young, and possibly bullied, these runners are also seasoned competitors and national icons. The leading newspapers have been carrying profiles of them for weeks. Most have been stars since running in their high school ekidens [long-distance relay races], which are almost as popular in Japan as the university races. They are used to holding press conferences, signing autographs, and dealing with the attention of female fans.”

But of course, the hype isn’t for nothing. Now they have to show us what they can do. The marshals call the runners to the start. They form two quick lines. And then the gun goes and they streak off along the road. Almost immediately they disappear around a corner. And that’s it.

But of course, the hype isn’t for nothing. Now they have to show us what they can do. The marshals call the runners to the start. They form two quick lines. And then the gun goes and they streak off along the road. Almost immediately they disappear around a corner. And that’s it.

They’re gone.

The best way to follow the action is on TV. This race attracts 30% of the TV audience share over two full days. This is comparable to the Super Bowl in the US and more than the FA Cup final usually gets. I’ve managed to get a press pass for the race and so I clamber into the media bus, where the race is being shown on an onboard television. I settle down for the ride to the lakeside town of Hakone, where the race finishes at the end of the first day.

On the screen, the runners are bunched up in a big group. The commentators are complaining that it is a slow pace, but in fact they’re running at less than 60-minute half-marathon pace, fora 21.4km leg (almost exactly a half-marathon). Incredibly, all 23 of the runners in the race are going at this pace, which is well inside Japan’s national half-marathon record.

The fact that all the runners have gone with the pace is what has thrown the commentators. This isn’t slow; this is insanely fast. The leaders reach 10km in 28m36s, which is a 10km personal best time for most of the 10 runners still in the front group. And they’re still not even halfway through.

In the end, they slow down, but the first leg is still so fast that the first three complete the course in a time equivalent to a sub-61-minute half-marathon. Only four Japanese men in history have managed that in a half-marathon, yet here in Hakone, three students have done it on the first leg. And they haven’t even broken the stage record. And most of the teams’ best runners are still out on the course waiting to run.

The gauntlet is well and truly hurled down, and as the second-leg runners head off on their way, they have a lot to live up to. But this is how ekiden, and in particular Hakone, works. Each performance inspires the next athlete to run harder. They thrive off each other. This is it: the race of their lives. There’s no holding back. They are prepared to within an inch of their lives; they have the hopes and efforts of their teammates on their shoulders, and they have the nation watching. They run like they will never run again.

All the race’s 10 stages are close to a half-marathon in distance, and over the two days an incredible 30 students run a half-marathon equivalent time of less than 63 minutes – and that’s excluding the times on the race’s fastest sixth stage, which is mostly downhill.

For comparison, among British runners, only three men ran a half-marathon in less than 63 minutes during the whole of 2014.

At every changeover, the effort and emotion of this race is etched across the contorted faces of the runners. They seem to run with their eyes closed, their mouths gnashing. Even their hair seems to be getting in on the act, straining from the tops of their heads. As they pass on the tasuki (a ribbon that acts like a relay baton), they tumble to the ground and are helped up by comforting teammates, who wrap jackets and towels around their broken bodies, their faces twisted, sometimes openly weeping with the effort. It usually takes two people to hold them up. A marshal, too, is usually on hand, giving them air from a handheld canister, fixed over their mouths, though they hardly even seem to notice it through their tears.

Normally Japanese people baulk at even shaking hands with each other, preferring the restrained dignity of a little bow.

Expressions of emotion are rarely on public display. But here, the waiting teammates are clearly concerned and do their best to comfort and help their companions, with loving arms around their shoulders and kind words whispered in their ears. Seeing this spirit at the end of such genuinely incredible performances, with the whole country watching, feels like stealing a tiny glimpse into the collective soul of Japan. The raw emotions, the companionship, the drama. I feel almost uncomfortable standing there watching, taking pictures with my camera, as though I’ve gate crashed an intimate family occasion.

At the end, I see many of the fans, who are mostly young women, crying. When I ask one woman why she likes Hakone so much, she can barely speak. “It is so moving,” is all she can say, biting her lip I leave the next day realising that every other race I’ve ever witnessed up until now was like a football match played out in front of a half-empty stadium. Here, though, the stadium was full, the noise was deafening. This was long distance running as a blood-and-thunder sport, where every last competitor was willing to break himself to keep up.

It really was fantastically epic.

Adharanand Finn is the author of Running wıth the Kenyans and The Way of the Runner (published by Faber & Faber), which is out now. @adharanand

Luke Waller is Mr Smile Himself, Semi-Pro Footballer, Amateur Politician, Weekend Historian, Fulltime Illustrator. Luke is the only person in the world to have illustrated the first ever cover of Like the Wind magazine and you can buy his beautiful prints in our shop. www.LukeWaller.co.uk // @LucaXun