This piece first appeared in issue 19 of Like the Wind.

Words and photography by Barbara Kerkhof.

HE MIGHT NOT MOVE LIKE SUPERMAN. HE DOESN’T EVEN RUN – OR WALK – LIKE WE ALL DO. But John Jansen lives for running like nobody else. And that is what makes him the coach all of us could use.

My husband Dirk used to be an athlete. He was a 2h19m marathoner, lean and fast as lightning (to me). But with three kids and a demanding job, he totally lost his running mojo. Instead of grabbing his trainers day after day, he grabbed the remote control and stared at the television. It looked like he would never, ever run again; I couldn’t even mention the word to him (and since I am a runner myself, that was pretty hard to avoid). But one day in summer 2017, he went for a little trot and met another runner who was going through the same process. They eventually ran a marathon again, together (in less than three hours – that’s what I call a comeback).

That dude introduced my husband to a guy named John Jansen, a running coach in our home town in the Netherlands. Dirk went to have a coffee with him and returned home with a spark in his eyes. The spark soon became a fire in his soul, lit by the vision of this new coach. Obviously, I was starting to get curious.

WHO IS JOHN JANSEN?

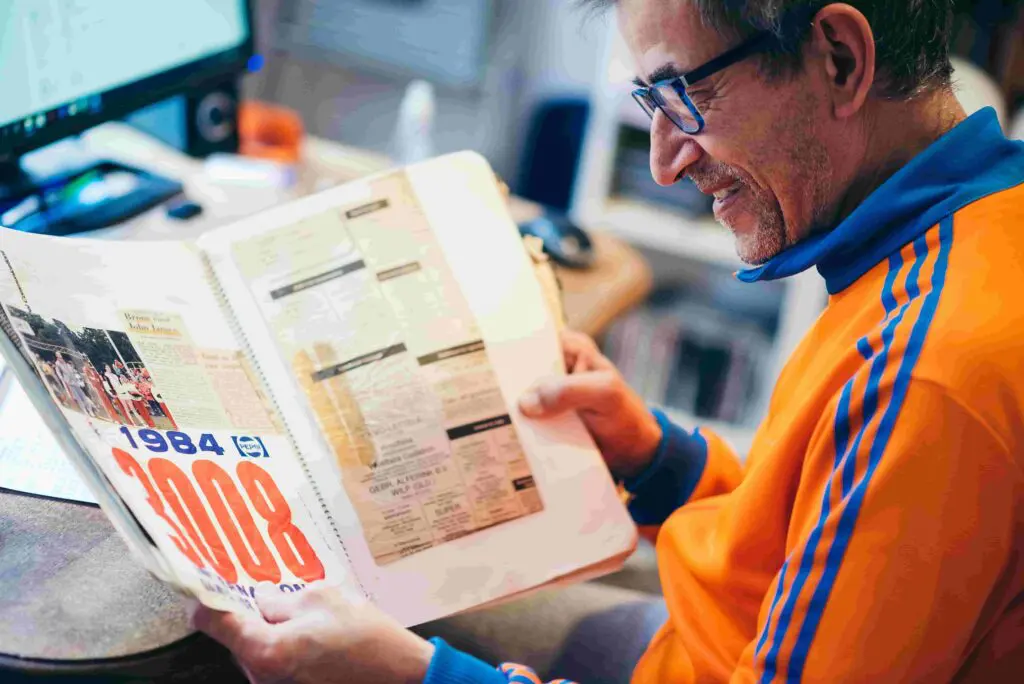

Whoever sees him walking down the streets, or stumbling along the track, wouldn’t suspect John Jansen was once an Olympic athlete. You may think he’s a bit (or very) drunk, or at least not well. However, he won a bronze medal at the 1984 Paralympics in LA and he has a personal 10km best of 38m50s.

Jansen was born prematurely (after only six months of pregnancy) in 1964 as the youngest child of 13. His sister died when he was two years old; his father passed away when John was four. When his brother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, the doctors tested all the siblings. It turned out all the others had a rare disease that may have had a bearing on their MS and also caused severe kidney problems. John had his own troubles: he had cerebral palsy and not only had to deal with spasms but contracted meningitis when he was four. “I know I’ll live to be at least 100 years old. I just know it,” he says now.

At school the teacher put him in a corner with Lego blocks while teaching the other kids how to read and write. Eventually John didn’t want to go to school any more – when his mum found out, she was furious and insisted that her youngest son would be taught like the other kids. It turned out little Johnny wasn’t retarded, but deaf on one side and nearly blind. He got a hearing aid and glasses and the world looked totally different. From six until II years old, he went to boarding school where he was beaten by his gymnastics teacher. “But really,” John smiles, “I feel like I had a good childhood after all. And I think that no matter how hard life is, it can never be an excuse for misbehaviour.”

John vs life: 5-0.

“IT MAKES ME MAD WHEN I SEE ATHLETES WASTING THEIR TALENT”

FROM PING-PONG TO RUNNING

“I used to play football and ping-pong at school. I sucked at both,” he recalls with a grin. “My teacher needed a runner for a team and he decided I was going to be that runner. He had me training four times a week and soon I could run in a straight line instead of wobbling from left to right. I placed fourth in the world in a [parasport] cross-country race. That’s when I became an athlete.” He joined a track and field club and met trainer/ athlete Honore Hoedt (who later became a trainer for world-class athletes such as Sifan Hassan). He said to John: “I don’t know anything about sports for the disabled, but when you fall you have to get up and go on, all right?” That was the beginning of a long-term friendship (36 years now).

“Honore was my teacher in many ways,” John says. “He was more than my running coach; he helped me get a key to the front door of our house, for example – like all my brothers and sisters had. He showed me what high-level sports meant. There was only one way to go: onward! He made me what I am right now and I am grateful for that.” In 1984, John won the bronze medal in the 1,500m cross-country at the LA Paralympics; in 1986 he became European champion over 1,500m on the track.

“A RUNNER NEEDS TO SHIFT THOSE GEARS, AND USE ALL OF THEM DURING TRAINING”

THE FIGHTER

“I have always had to fight for everything I ever wanted to accomplish,” John says. Could that spirit have something to do with the fact that he had already fought for his life twice, through premature birth and meningitis? “Giving up was never an option for me. That is the reason why I am ruthless with my athletes. The spasms I have make me fall down all the time. So when one of my runners complains about having a bad day, I think: shut up and run! It makes me mad when I see athletes wasting their talent.”

Expectations after LA were high, so it was a nightmare to finish in fourth place in Seoul in 1988. “In LA I was a nobody; in Seoul I had something to prove. That fourth place made me so mad that when a Japanese film crew didn’t get out of my way at the finish line, I threw my puke at their camera – of course I got fined for that.”

THE STUDENT

After ending his career as an athlete, John studied to be a coach. After completing the first course he was told he had reached his personal boundary. But, being a fighter, he took all the other classes and learned everything there was to learn about running, hurdles and sprinting. As a coach he thrives on conflict. “I like to stir things up, awaken their angry side to help them succeed. It doesn’t make them smile, but it toughens them and teaches them how to tone down.”

When John quit his career as a runner, he was pulled into a huge black hole. One brother died and he had a gambling addiction to deal with. But he fought, of course he fought. Another brother, Robbie, who was a lawyer, helped him out, but on one condition: “I had to take every track and field course there was.” A couple of years later he had paid back all his debts and one of his pupils became a national champion.

John vs life: 8-0.

THE DREAM

“My biggest dream in life is that one of my athletes will go to the Olympics. Athletics is what matters most in my life.” John is a 54-year-old single guy who lives in a typical man-alone-apartment with his little dog Cato. Sometimes he gets yelled at when he walks Cato; people even throw fireworks at him – just because he walks differently than we do. He cares more about his athletes’ running shoes than about eating his own vegetables. He is on standby for his runners 24/7. And that works the other way around, too. When going on a training trip to Germany or Portugal, the athletes make sure his tricycle comes along (he cannot ride an ordinary bike). One of his fastest athletes, the 26-year-old student Wouter Ploeger, stays over at John’s house every fortnight to train with him, to discuss his programme and he makes his coach some proper meals. He walks his dog when the streets are slippery in winter.

Athletes and friends invite him over for Christmas at their family homes – he spent Christmas 2018 with us and our kids. He also had Christmas dinner with Wouter and his parents. “We trained; testing lactate on Christmas Day is something really special, I think. It inspires me. I used to take running way too seriously, but now I know how to enjoy other things in life, like having a beer with friends while still running fast.” When John and Wouter cheered on their teammates in the Frankfurt marathon, John leaned on Wouter’s shoulder. “He’s embarrassed, but I won’t let him be,” Wouter says.

“I KNOW I’LL LIVE TO BE AT LEAST 100 YEARS OLD. I JUST KNOW IT”

JOHN’S WAY

John Jansen sees the human body as a gearbox: “A runner needs to shift those gears, and use all of them during training.” I remember Dirk being confused when he started working with John. In some runs, the pace was much slower than he’d ever run before. But then again, other runs were exceptionally hard. John is a coach who is really present. His programmes are custom-made for each athlete and he evaluates them after every workout. He watches his athletes when they run, not his phone. He gives his athletes the freedom to think about the programme, but wants them to contact him when they make changes. “I offer my runners a warm bath. I approach each one of them as an individual – in my opinion that is the key to success,” he says.

And success has many faces. For my ex-couch-potato-husband, it means he regained the joy of running, the joy in sharing a passion and running a marathon in 2h46m. For Wouter Ploeger, it means coming back from an injury and running 3m40s on the 1,500m again. Success could also mean one of the younger athletes in the big pool of talent with which John works with makes it to the Olympics. That would really be John vs life: 10-0.