This article first appeared in issue 22 of Like the Wind.

Words by Danny Bent. Photography by Clement Hodgkinson and Tom Baker.

Nine hours into our adventure, I found myself sobbing into my soaked gloves. Tears streaked my face as I realised what we’d taken on. As group leader, I was supposed to be the positive energy. The person who inspired a rag-tag bunch of runners to take on nine marathons (or ultramarathons) in a row, from the north coast of Iceland to the south across one of the planet’s most brutal landscapes: a place where weather changes in an instant and the force of rivers sweeps 4x4s away like toys. More tourists die in Iceland than residents.

Before arriving in Iceland I’d been inundated with messages from the runners, mates who had replied to my facebook request for an adventure. I knew all bar one as friends – they mostly came from events and groups I’d spearheaded: Project Awesome, One Run for Boston or London Relay. They were telling me they hadn’t really trained. Work had taken over, or relationships, or just plain boozing. Most hadn’t run a marathon before – only one had taken part in a multi-day ultra of the kind we were taking on. But I wasn’t worried – I make a living speaking to businesses about human potential, so I knew each individual was capable of doing this.

I repeatedly told them: “You’re going to ace this, don’t worry.”

I maybe wouldn’t have chosen those words if I’d known what lay ahead.

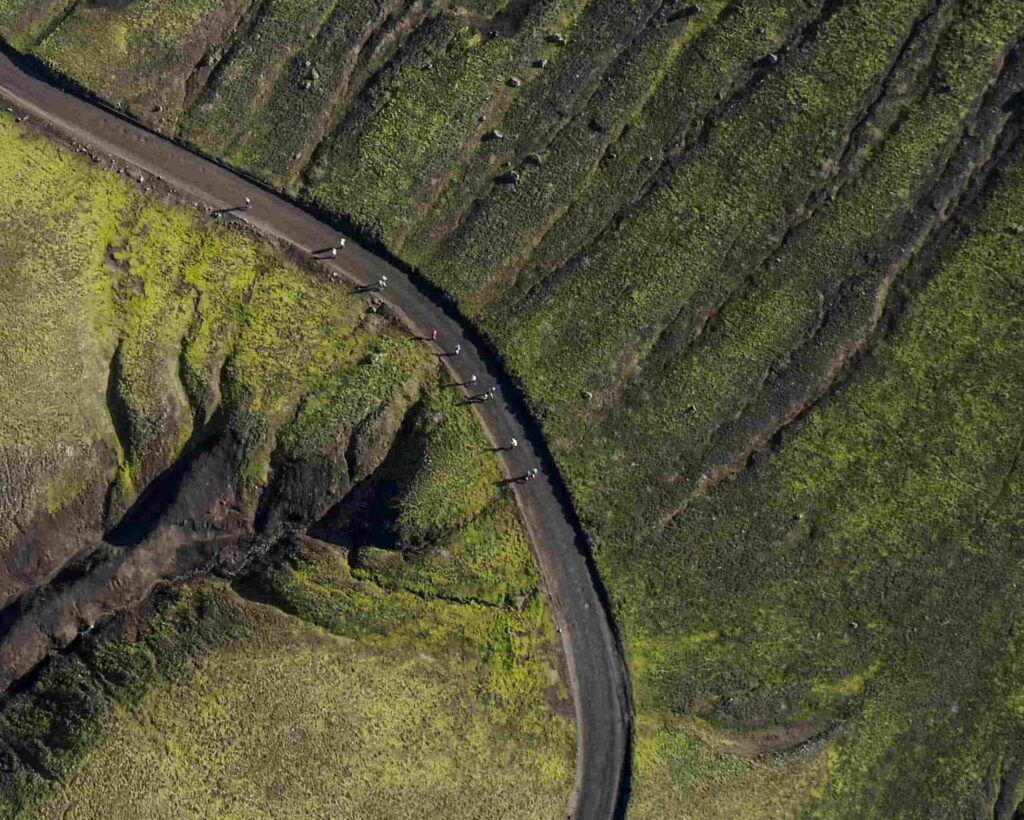

Who doesn’t want to run across Iceland and see some of the beautiful country that others don’t get to see? Iceland is mind-blowingly gorgeous but we wanted to go beyond the familiar tourist paths of the Golden Triangle (or Golden Circle, if you prefer). We’d been planning to run the F26: a rugged route that cuts the country in half, passing between the two largest glaciers. Nick, who was going to be in the Land Rover following us, had meticulously worked out our route, camping spots and feed stations.

Nick and I haven’t actually known each other that long, but when we started chatting about life, I mentioned how I wanted to organise a challenge in Iceland. He said: “I was just planning the same.” As well as Nick and I, there was Nick’s wife, plus the photographer, the videographer… and 18 runners.

A week earlier, we’d heard that our planned route was closed. I just thought we’d do it anyway. But when we arrived in Iceland, we heard there was deep snow on the highlands and the rivers were running fiercely. The Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration said that the rivers we had to cross would wash away the Land Rover – and certainly the humans. Huddled around a map and compass, the morning of the day we had originally scheduled for double-checking all the kit, Nick and I tried to work out what to do. All the other runners were in bed nursing hangovers after a karaoke bar decided to give free beer to anyone who sang a song. It seems my pals aren’t shy of a singalong…

Nick and I got in the Land Rover and in one day travelled 600km over mud, rivers and rock, in search of a second route. Nick was planning in six hours what he’d planned in six months. The course was nowhere near as beautiful, but it was safe.

Then – with the coach poised to set off to take us to our new start position – the F26 opened. All roads showed up as green on the map. We gathered the runners and explained our predicament: the epic route was liable to close at any time. The safe route was going to stay open but wasn’t quite the same. Our oldest runner – Brian, a 58-year-old ex-smoker and drinker who’d lost half his actual body weight since taking up running – stood up and said: “We signed up for something epic. Let’s go epic.” As he stood there and saw heads nod I was filled with such pride. Pride in the group, in my faith in humanity. When I wrote the facebook post I knew this event would only attract the finest of humans.

With a smile on my face I stood by the Land Rover while everyone brought out their bags. The pile increased, bag by bag, until it was about as tall as the Land Rover. As we strapped bags precariously on to the roof – doubling the vehicle’s height – I quietly started to question what we were doing. Again.

So we set off on day one. Within a kilometre, one of our runners, Tia, had an asthma attack. I asked where her medicine was. She replied: “At home.” I kicked myself for not having asked people to fill in a medical form. It turned out this person hadn’t actually ever run in her life, and I kicked myself again for not having asked about experience before we set off. This first day was 26 miles and the second was 30 miles. As the day progressed and my mood worsened, my mind was plagued with potential worst-case scenarios: someone wandering off course and getting lost, dying from the cold, being washed away by a raging river, support vehicles getting stuck in the snow or a medical emergency we couldn’t support. I became obsessed with the thought: “We’re going to kill someone here.” I spent several hours beating myself up, giving myself abuse for my ridiculous behaviour.

I pulled Nick aside and we sat in the 4×4, where I unleashed all my fears on to him. How had we been so stupid? How had my quirky brain ever considered this to be a good idea? Nothing is worth killing people for. Tia could have another attack miles from support and even further from a hospital. We had to pull the trip. We should go back to Reykjavik and take trips along the Golden Triangle in the car to see the sights. These people were just average Joes, working a day job, having a drink on Friday, maybe doing a Tough Mudder on Sunday – we’d taken on an expedition at which fully trained adventurers would raise their eyebrows.

By the end of day two, Tia had realised this was a step too far and jumped in the Land Rover to catch a bus back to Reykjavik. With her departure, some of my anxieties disappeared. During day two, people had smashed their most ever miles – and they were still smiling. But by day three, the mood had changed again. People struggled in, starting to feel the pain from three days of straining their muscles. As I and a couple of front runners got in, rather than sitting down, we were called into action: a storm had whipped up and was trying to blow the mess tent away. We tied it to the Land Rover and trailer and held on to the legs.

We’d got the water on for the dehydrated food (pretty much our only source of calories… and we were already absolutely sick of it), but it was getting mixed with the black sand that was being blown everywhere. There was no way we were setting up the smaller tents here: they’d be flying all over Iceland. Hanging on to a tent pole, I was hating every moment. Not my own response to this situation, but the worry for everyone else. This mess tent was barely large enough for us all to stand and eat in, let alone sleep. But as the runners came in they used their initiative. They ran back out into the raging storm, their exposed hands, faces and legs being peppered with the sandy rain, and came back with large stones that they used to weight the tent sides down. They must have carried a tonne between them. I couldn’t believe my eyes – they were smiling too. Some were laughing. They were making the most of this opportunity. They were pulling together. The tent stabilised. We ate and cheered each other for getting this far, then we rolled out our mats and sleeping bags and filled the whole floor of this tent with people. Not an inch was spared.

In hindsight, this was my highlight of the trip. Lying face to toes. Sniggering when someone farted, saying goodnight to everyone, laughing whenever someone needed a wee and they trod on your legs, face… balls. It was this point that I realised that this group of exceptional people was going to do anything to get as far as it possibly could. No matter what. We crossed rivers arm-in-arm to stop people getting washed away by the current, the Land Rover disappeared under water at one point, ice storms tore at our faces, bruised ankles looked like elephant legs, balls the size of eggs swelled out of shins… but we kept going.

Beatriz was the slowest of us and her legs were in pieces, held together by tape. She hobbled along, rattling with the amount of painkillers she’d consumed. If Nick pulled alongside her at any point she’d turn sweetly and, with a smile, say: “I’m not getting in the fucking van.” That was the attitude.

At the end of the seventh day we pulled into our camping spot and there was a tiny hut. I opened the door and inside was an Icelandic lady, who greeted me politely, “Halló”, but I was unable to reply. Behind this lady were cookies and crisps and cola. We bought everything and devoured it in minutes.

There were hot water springs nearby, so we visited to allow this new food to settle and to ease our muscles. We also had three beers left over from the karaoke night. We shared them in the hot springs, having a sip and passing them on. Again, blown away by the togetherness of this group, I realised we were going to make this. As that beautiful image filled my mind the skies came alive, as if expressing this new energy I was feeling. The Aurora Borealis streaked across the sky, swirling and dancing with itself – it felt like it was celebrating what our group had achieved. We ran, walked or limped our way through the final two days and, as we got closer to the end, emotions showed. Tears were a frequent sight as the runners took each step nearer to the finish. I also felt the emotion of being almost there. Exhaustion, pride and relief combined and I cried at any nice gesture anyone made. I heard “This has changed my life” from half the people; others suggested it had shown them they could push beyond their perceived limits and that they’d be going home and reassessing their limits in other parts of their lives.

The crazy thing is they credited this achievement to me having faith in them. The guy who, on the first night, wanted to cancel the whole trip, sure that we wouldn’t make it. I was very quick to point out that we made it together and that without any one of this newly formed tribe, the whole group would have failed. But I did allow myself to take some of these lovely words to heart and thanked my quirky brain for giving me this faith in human strength and endurance in the first place.

Nick and I are already planning to take a new group to Iceland in 2020. We’ve learned a few lessons, it has to be said.

Danny Bent is a keynote speaker on happiness, leadership and human potential. His natural habitat is running in the mountains or jumping into a freezing river in the nude. TW: @dannybent / IG: @danny_bent

www.dannybent.com / www.greatnorserun.com